Tornado the Robot

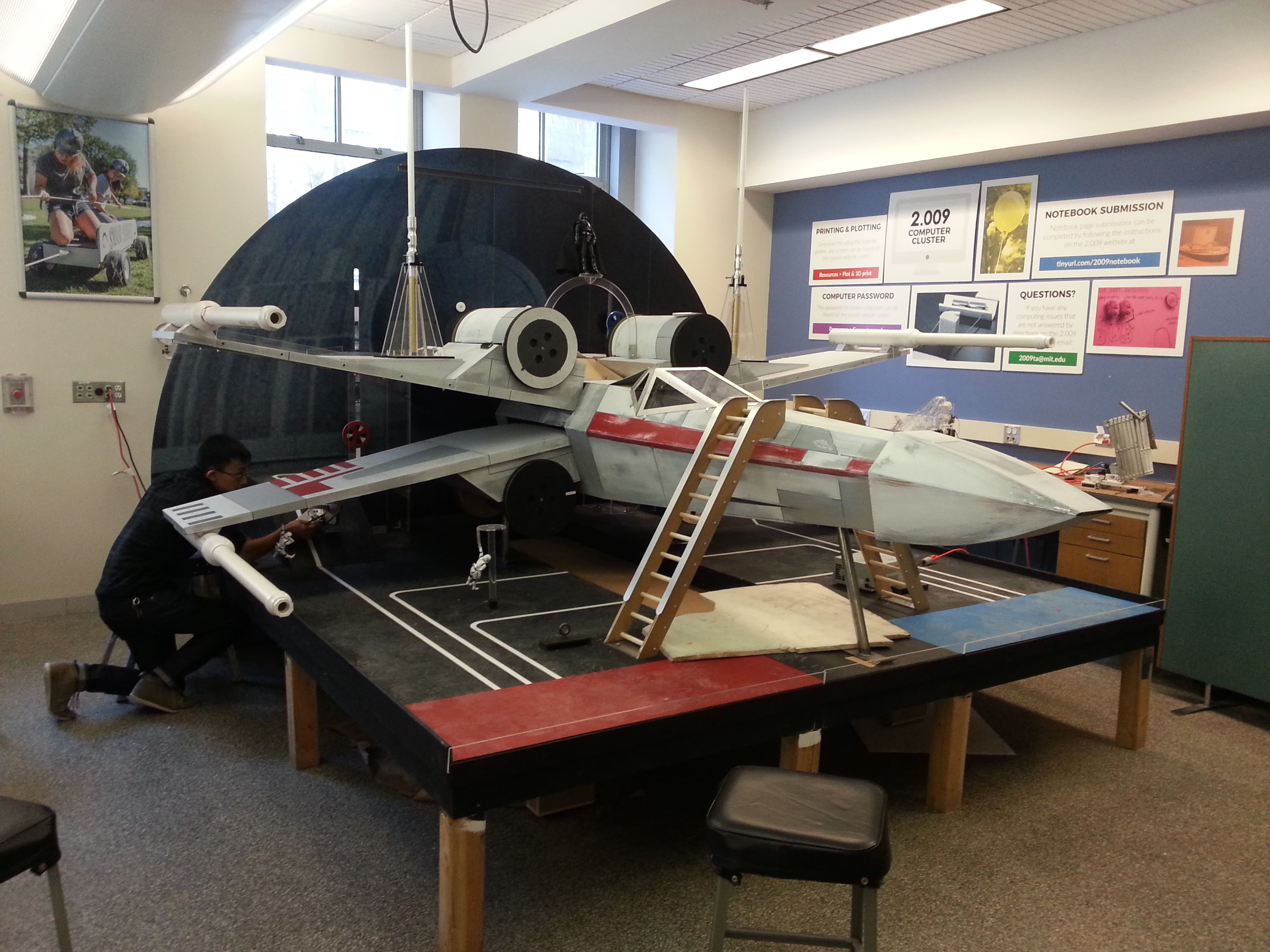

Game Board

This class was based off of designing robots to score on a game board, and is basically the foundation for the FIRST robotics competitions. This year, our game board was Star Wars themed! Points could be obtained by collecting stormtroopers, lifting 3d prints of the professors out of the carbonite freezers, and spinning up the x-wing turbines in preparation for liftoff. A point multiplier will be applied to any round that tilts the lightsabers on the upper wings.

Creating a winning strategy

After examining the scoring algorithm, I realized that spinning up the turbines to full speed gave a higher point score than most of the other options combined. Just spinning the lower turbine to full speed autonomously ended up giving more points than the entire rest of the board combined - so I realized I had to be able to spin at least the lower turbine in order to go anywhere in the final competition. As there is a 90 second time limit, focusing on a few strategies and doing them well has paid off in past competitions.

Drive Mechanism

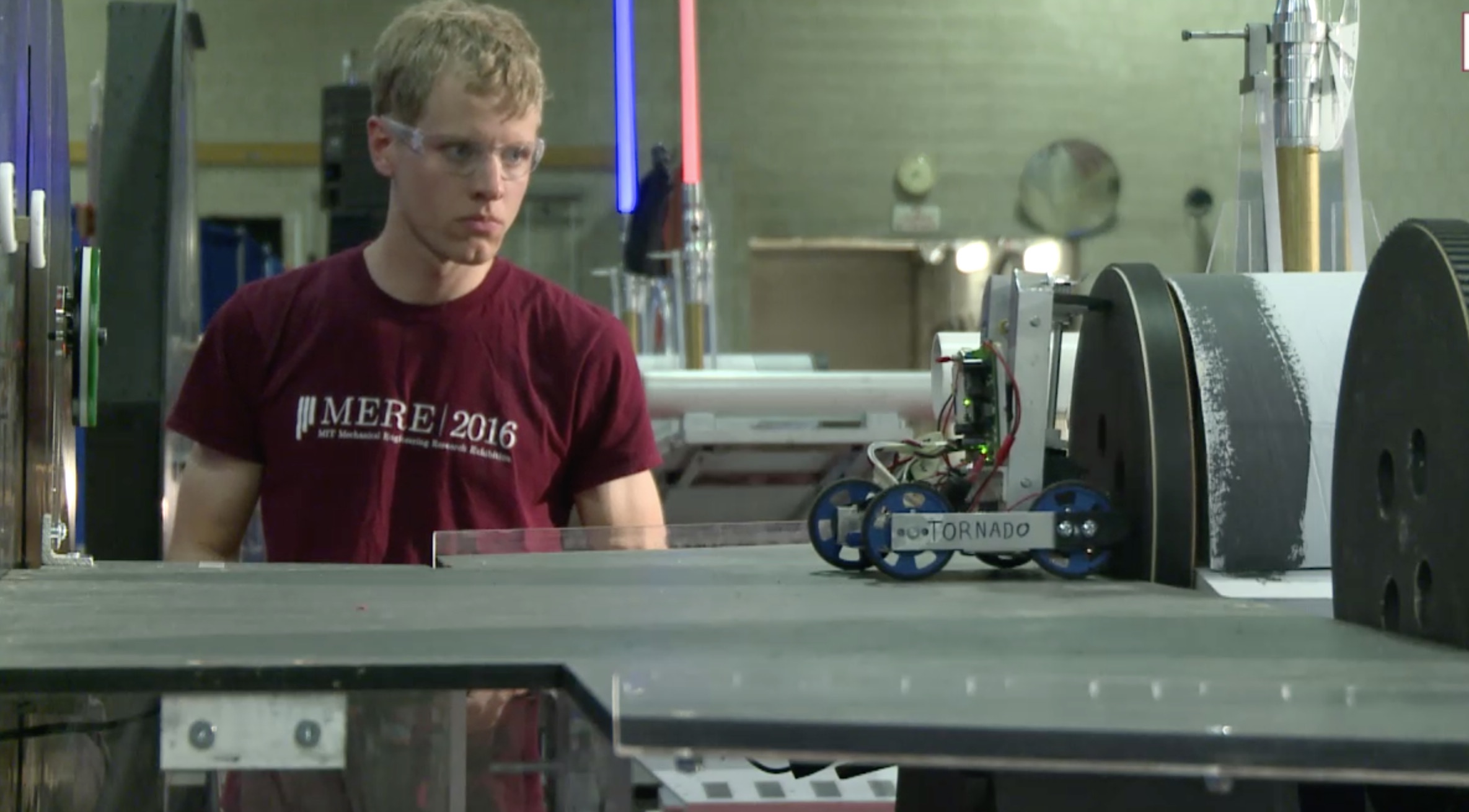

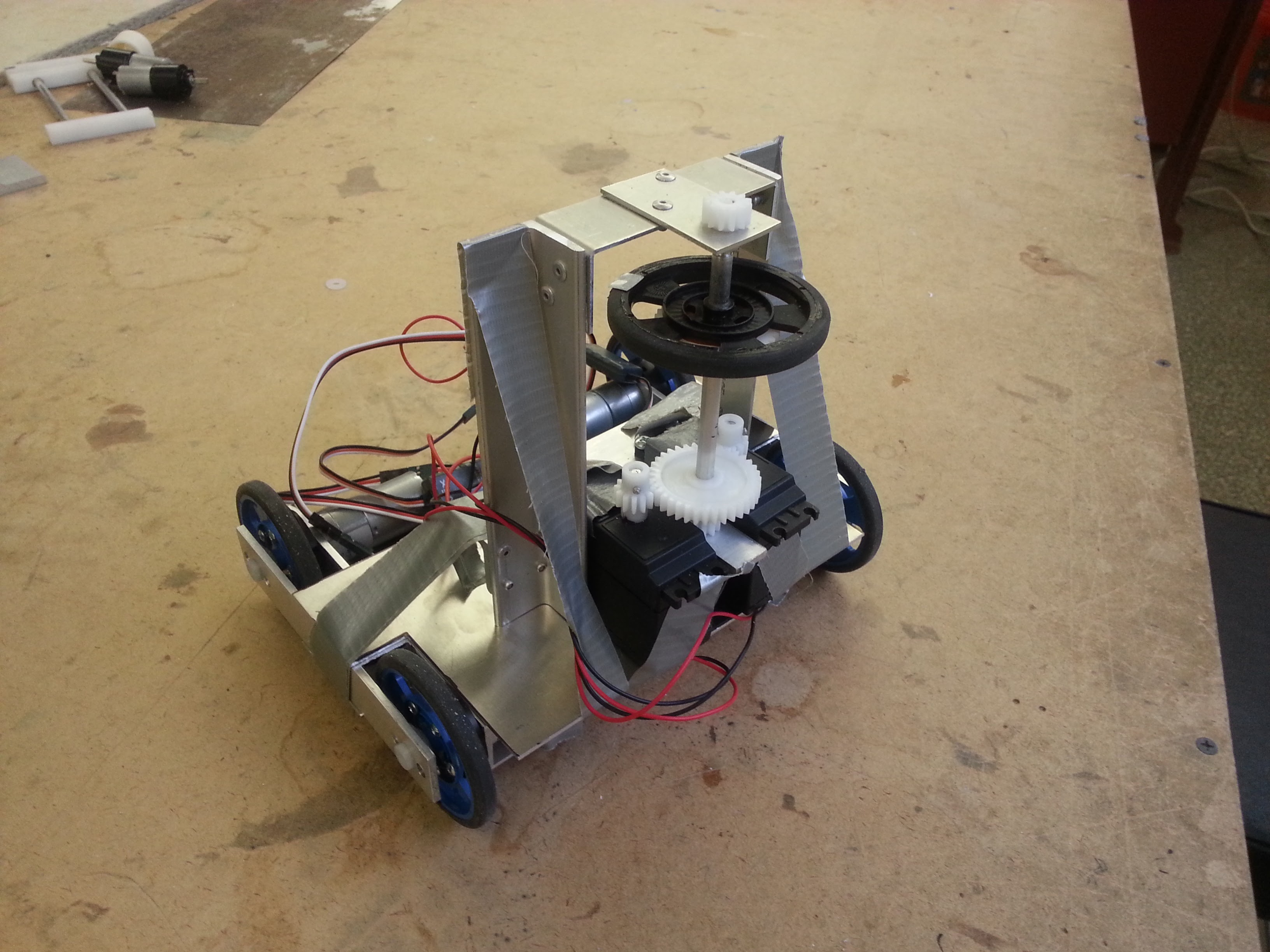

I wasn’t expecting to, but I ended up pioneering a drive strategy that was widely copied in the second half of the class. Rather than try to engage the sides of the turbine (where alignment is difficult), I realized I could engage a rubber wheel on the face of the turbine. The efficiency is slightly less than ideal, as my drive wheel and the turbine are rotating on axis at right angles, but if I over-specced the power by about 20%, I could tolerate up to about 1.5 inches of misalignment from the center and still spin the turbines to full speed on time. Extended testing resulted in my drive tire heating up, smelling, and wearing down, but a good burnout before a run improves traction anyway. I kept some spares on hand and replaced tires as needed.

The upper and lower turbines are mounted at different heights from the floor, but after some careful measurement, I realized I could engage the lower face of the lower turbine and the upper face of the upper turbine at the same distance from the turbine axis without changing the height of my drive wheel. As an additional bonus, I could engage the elevator switch with the same wheel, allowing me to concentrate on just one mechanism to accomplish three functions.

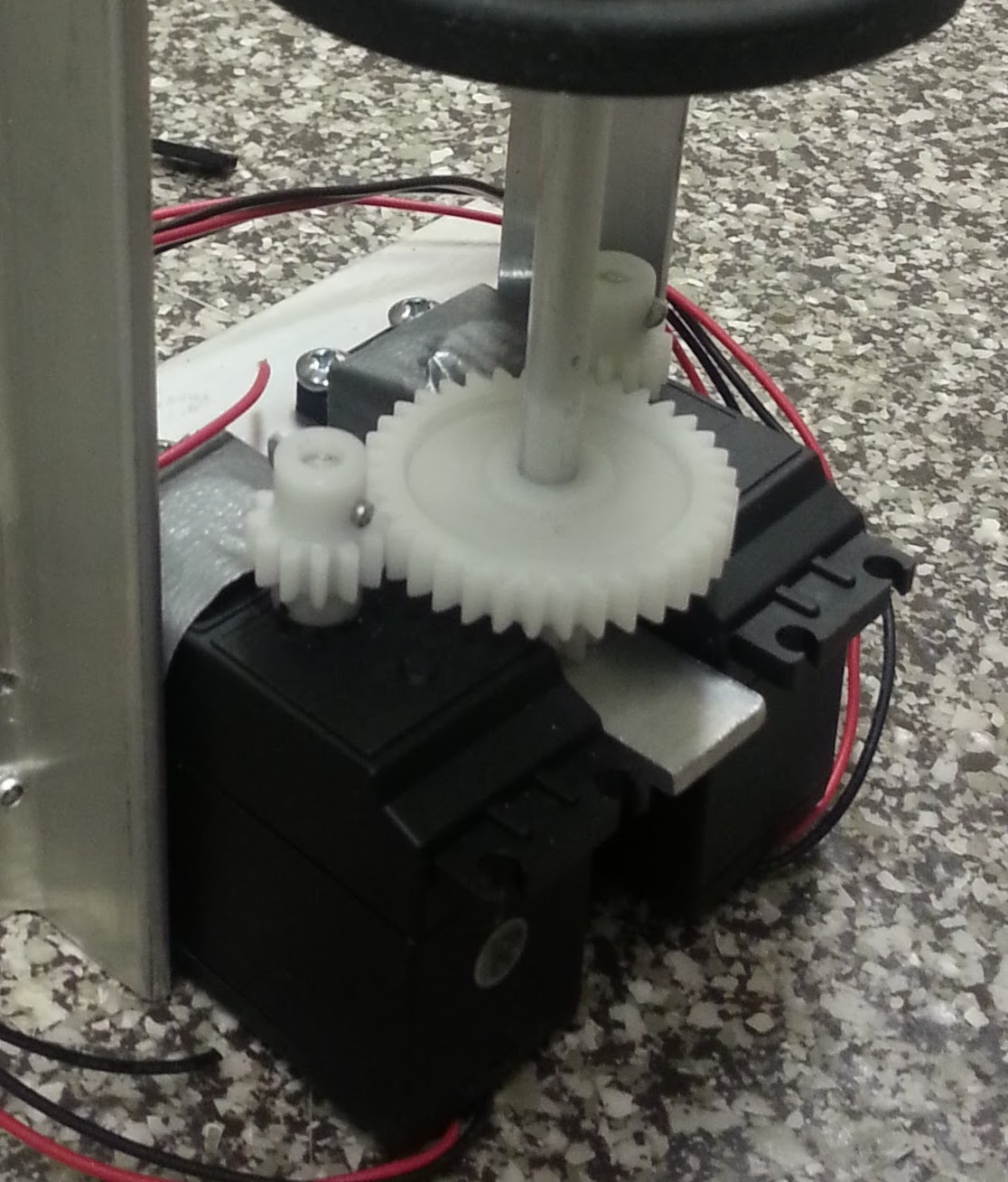

Gearbox

My drivetrain strategy posed one unique problem: I needed to spin a drive wheel at over 350 rpm, and my analysis stated I needed to use at least 2 of our most powerful motors with little to no gearing losses. These geared motors only operated at a no-load speed of 52 rpm. Alternatively, I could remove the gearbox and operate at around 10,000 rpm, but neither of these options came close to the speeds I needed. The lab banned the use of ball bearings and a 2 stage gearing with journal bearings from 52 up to 350 rpm would lose an excessive amount of power. So after some careful math, a little bit of duct tape, epoxy, and some really careful case surgery, I took out the main drive shaft on my geared servo and installed my own bushing set to take power off halfway through the gear train. I then placed two of these motors side by side and put it through some brutal testing to make sure it would hold. Post-testing teardown showed no wear or deformation, so I reassembled and was ready to spin some turbines.

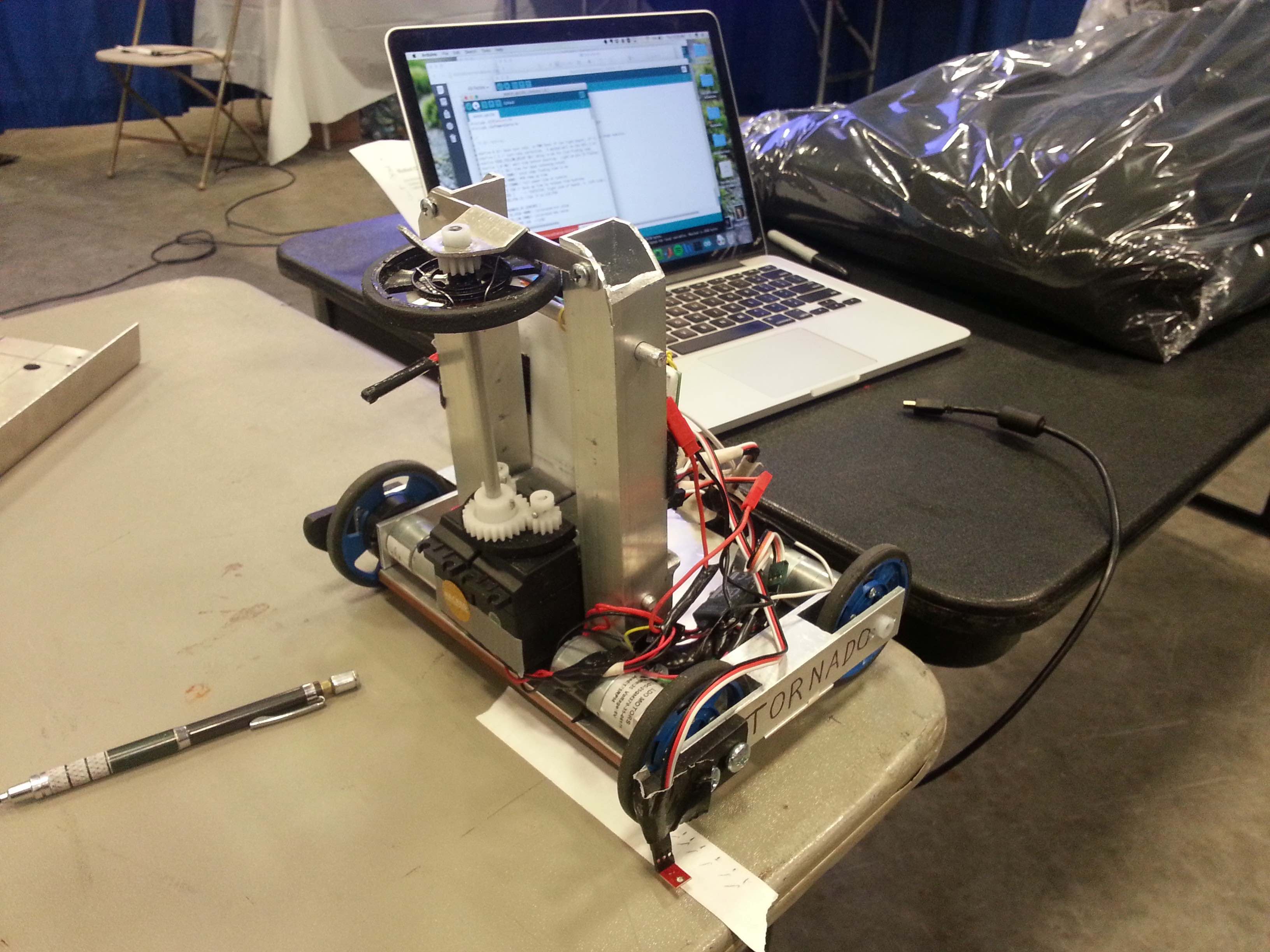

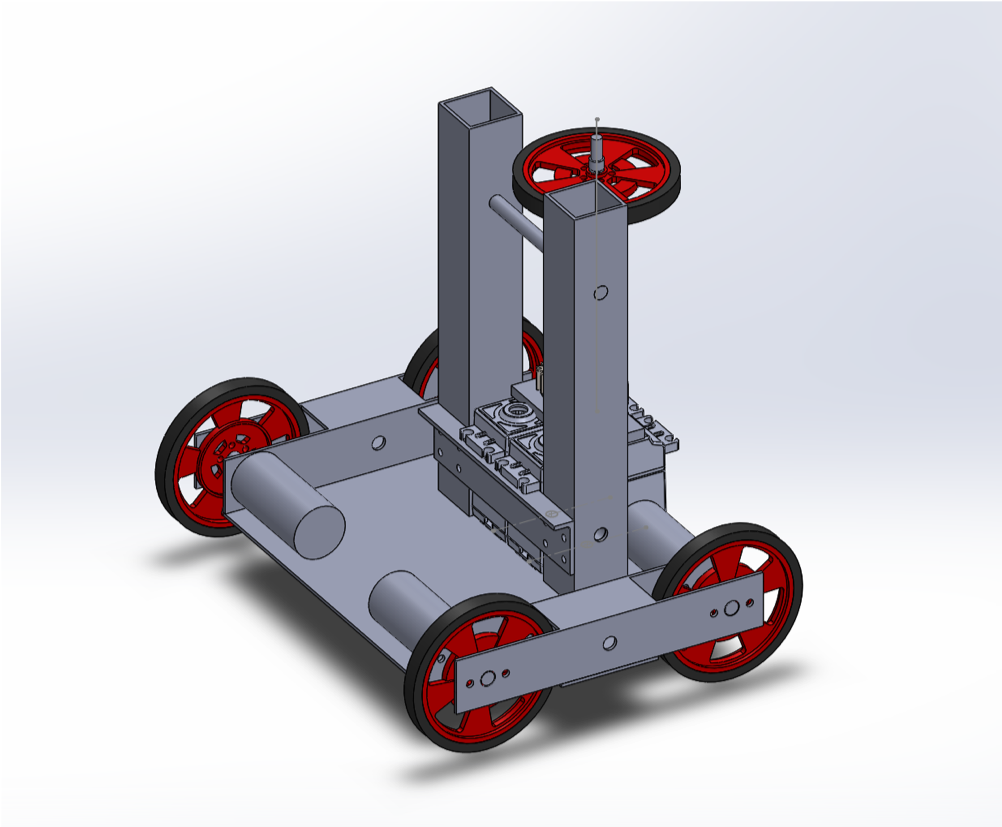

Drivetrain

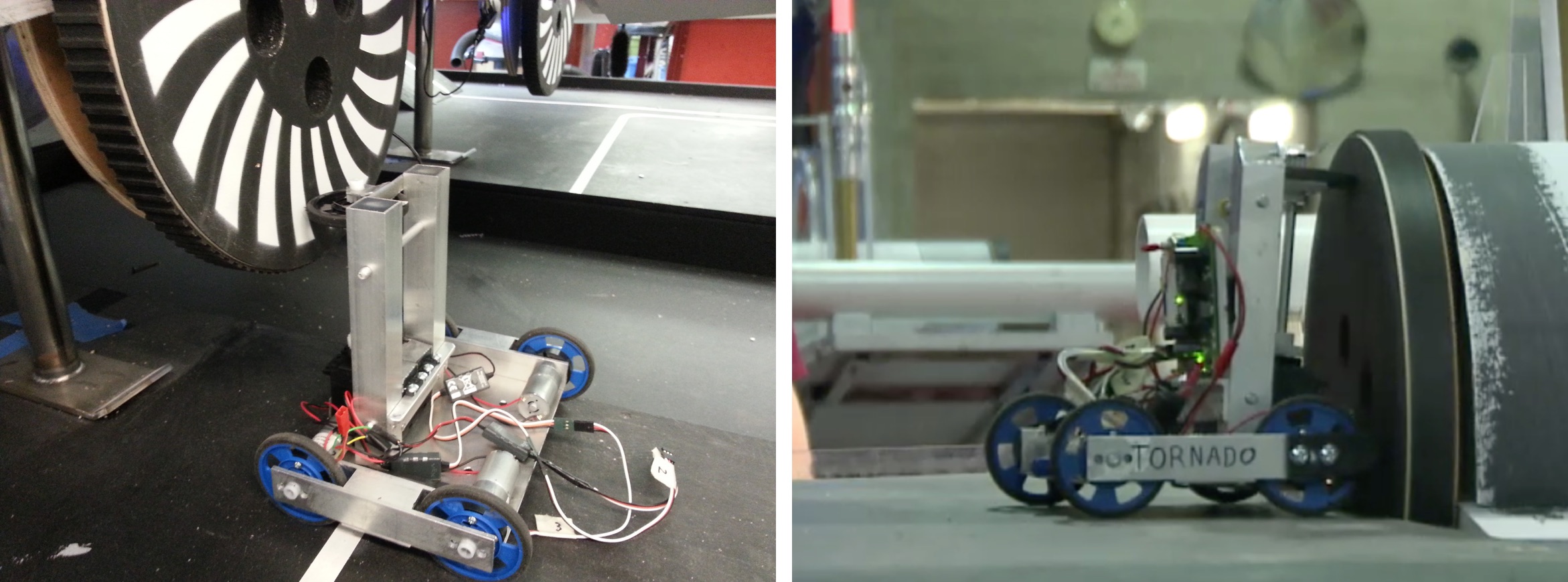

I initially wanted to mimic the drivetrain from a skid-steer loader because I knew this provided a very robust and manuevarable drive platform. But before making the final decision, I did a bunch of math to consider the restrictions on physical space, reaction forces from my drive mechanism and the optimal way to control for all of these variables. My analysis suggested that I build a vehicle that was wider than it was long with about a 3:2 width:length ratio. With this layout, a skid-steer drive with four wheel motors worked quite well and there was no need for the complexity of a more advanced steering system. Here’s one of the earliest test versions with the drive mechanism.

Algorithm Development

Any points that were earned during a 30 second autonoumous period at the start of the match carried a 1.5 times multiplier, and any turbine brought up to speed by the end of the autonomous period earned points for both time blocks, resulting in a 2.5 multiplier with no time penalty – as long as autonomous operation could be achieved.

There were no on-board guides to help autonomous operation, but I found one edge that I could follow that started halfway across the board. As the entire board was painted black, IR sensors worked very poorly, and the best they could do is receive “kind of black” for on the board and “really black” for off the board. I needed a reliable algorithm that would

- Guide my robot with only this binary signal

- Operate by dead reckoning for the first 2 feet until an edge was available

- Find that edge and operate my robot with under 3/4 inch of tolerance – or the entire robot would fall off the edge and end the match

- Be time bounded by under 8 seconds, and take the same amount of time for every run

I ended up creating a simple algorithm that logged the time since the boundary was last seen, and started turning towards the boundary at an exponential rate until it was found. Every time the boundary was crossed, the turn rate was cut in half and the process re-started. After tuning this, I was able to start at over 2 inches off target, never cross the target by more than 3/4 of an inch, and stabilize within 2 feet down to imperceptible movement. Operating code is available here!

Game Night!

At the final competition, I ended up with the highest scoring robot of the night. I also had almost perfect reliability through the match, with only one sensor failure in the final round that took some points off of my autonomous score and cost me first place. My focus on just one actuator for 2 turbines and the elevator allowed me to refine and perfect my platform and paid off with a very capable and flexible robot by the end of the class.